In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic we have seen a very disturbing increase in student absences in our K-12 schools. It would be comforting to believe this trend is just a lingering impact of the pandemic, and that attendance will get back to the old normal over time.

Except this won’t happen, at least not all on its own. The reason is that the pandemic accelerated forces that had already been in motion for some time. And these forces are if anything intensifying, especially the increased use of devices by students and the related “disengagement” of students and parents from the life of the school. Poor attendance is the biggest symptom of this larger problem of disengagement.

Remember how in the days of the pandemic we used the phrase “the new normal?” Well, disengagement and the related increase in absences is part of that new normal. And we are now stuck with this problem—unless we work proactively to fix it.

Except our focus here is technology. So, what does battling absences have to do with technology? Well, the powerful forces the pandemic accelerated were partly related to technology, such as our kids’ increasing attachment to devices. And, some of the solutions we need to apply to address this problem also make use of technology.

Let’s briefly consider how technology helped cause this problem, and then concentrate on how technology can begin to help to fix it.

Increased “disengagement” has brought about poor attendance.

There has been plenty of attention paid to the problem of attendance in a variety of media. Education-oriented media such as Education Week have been working for some time to draw attention to this problem. And on March 29 The New York Times had a great article on “Why School Absences Have ‘Exploded’ Almost Everywhere.” [i]

Kaylee Greenlee for The New York Times

The Times reported that since the 2019-20 school year the percentage of “chronically absent” students in K-12 school nationwide has doubled, from 13% to 26%. This problem is much worse in districts serving disadvantaged populations. In our Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS), the Times reported that between 2019 and 2023 the chronically absent rate went from 37% to 50%.

The Times noted that states use different definitions of chronically absent. For example, the State of Wisconsin defines students as being chronically absent “if they miss more than 10% of school days out of the total number of school days during which they were enrolled.” [ii]

In December, Alan Borsuk and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel featured an article on “What Are We Willing to Do about Low-Performing Schools in Milwaukee Public Schools and Beyond? Right Now, There’s No Real Plan for Change.” This article discussed the impact of disengagement and the related challenge of poor attendance. Alan used MPS’s Madison High School as a case study. [iii]

Many kids have simply stopped going to school.

What did Alan find at Madison? He found the school was orderly, and the administrators and teachers were highly motivated. And there were attractive programs in vocational areas, something too few schools offer.

Except there were far too many students in the building. At that point in the school year (mid-December) the average daily attendance so far was 58.6%, which meant that on an average day more than four out of ten students were not in school. In recent years more than 80% of the students at Madison have been labeled chronically absent.

Mike De Sisti – Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

He also reported that enrollment at Madison had fallen from 892 in 2014-15 to 625 in November of the 2023-24 school year.

There is also quite a bit of attrition as students get older:

- 224 of the Madison students were ninth graders, including 94 repeating their ninth-grade year.

- 180 were tenth graders.

- 134 were eleventh graders.

- 86 were twelfth graders.

What are the causes of this drop in attendance?

So, what is going wrong at Madison and at too many of our districts and schools across the nation? Part of the problem is families and students are often dealing with issues at home that become a barrier to school attendance, as we will discuss below in the case of the School District of Plano, Texas.

But a big part of our challenge is that many students and their parents have lost a basic force that success in school requires. This is the compulsion to simply make yourself physically come to school each day, as part of your larger daily—and lifelong—routine. Those on the education scene use the term “engagement” to describe a traditional connection to school, and the term “disengagement” to describe the loss of this connection.

As we noted above, this disengagement preceded the Covid-19 pandemic, although the pandemic intensified it in a variety of ways. Obviously, our kids can’t be successful in school if they aren’t in the building. We need to bring all our students and their families to once again be engaged in their school experience, and part of this effort is to bring about near-perfect attendance.

But this is a complex undertaking. Let’s focus on the challenge of addressing poor attendance.

Technology can address the problem of poor attendance in three ways.

Technology can help improve attendance in three major ways:

- The use of data analytics to help school staff and parents identify attendance problems.

- Top-down automated communication at the district and school level to alert parents of problems and encourage better attendance.

- Bottom-up one-on-one communication by teachers and other school staff, to intervene with parents of students with attendance problems.

Analytics can identify problem students and trends.

Student information systems (e.g., Infinite Campus, PowerSchool) contain reporting capabilities that allow districts and schools to obtain reporting on different aspects of the attendance challenge.

Examples would include:

- Students absent today at our school, both excused and unexcused.

- Students absent today for a second day.

- Students who are displaying more problematic patterns of attendance.

Districts and schools also need to develop data systems to track interventions that have been attempted with problem students and analyze the effectiveness of those interventions.

Top-down communication sends automated mass alerts to parents.

Top-down automated communication has been used for many years by districts to help manage attendance issues. This communication usually uses a combination of the district’s student information system and notification system software (e.g., BrightArrow, SwiftK12).

An example is that early each morning the notification system will extract data from the student information system on students with unexcused absences. The notification system will then send some combination of text, voice mail, and e-mail messages to the parents of these students. Note that these messages are generally sent in a single batch for the entire district.

Another example is to send alerts to the parents of high school students who initially were at school but have been marked absent in subsequent periods.

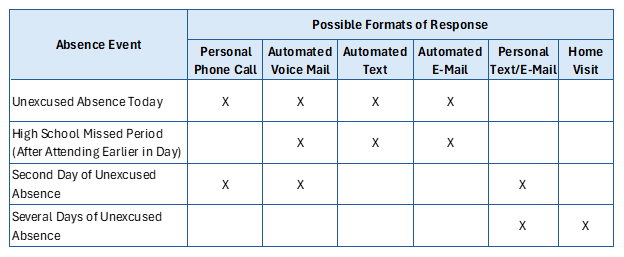

Additional types of alerts would include addressing multi-day absences. The chart below on “Possible Formats of Response” outlines some of these possibilities.

Bottom-up efforts make use of interpersonal communication.

But an effective solution to absences must go beyond alerting parents that their child is absent. The solution must also employ personal contacts with parents.

Such a contact may begin on the morning of the first absence, with a personal phone call from the school office in addition to the automated alerts. If attendance problems continue, calls from the child’s teacher would tend to be especially effective, due to the teacher’s personal relationship with the family. Families with persistent problems would benefit from a home visit.

Districts benefit from a comprehensive approach – Plano, Texas.

And districts would clearly benefit from a comprehensive approach to absenteeism and a unified overall management of the challenges. A good example would be the Plano Independent School District in Plano, Texas. Plano is a racially diverse district with almost 50,000 students. A recent Education Week article on “This Leader Takes a Compassionate Approach to Truancy. It’s Transforming Students’ Lives” profiled the district’s efforts to improve attendance. [iv]

Plano had been relying on the efforts of a truancy court to manage attendance. But sending families to such a court did little to address the problems underlying serious attendance issues. Sharon Bradley, a new Director of Family and Social Services, led the shift to the use of “tiered intervention strategies…to reengage students” and a shift to an attendance review board that would work with families to identify underlying causes for the absences and if needed develop a family support plan.

But there’s a larger problem, disengagement.

As the experience in Plano showed, there are often larger problems behind the attendance challenges of a family. As we noted above, part of the problem often includes a disengagement from the life of the school, and disengagement has gotten much worse in the aftermath of the pandemic.

In our next blog entry, we will try to tackle the challenge of disengagement. And as we work to maintain our technology focus, we will explore how technology contributes to disengagement, but how it may also help us in our efforts to reengage our students.

Have you had any success? What are your thoughts?

If you have any thoughts or contributions on the challenge of attendance, or on the upcoming topic of engagement, please hit “Leave a Reply” above to add a comment, or contact me at schulzj@jerryschulz.com.

And thanks to all for everything you do for our kids in these challenging times!

Jerry Schulz

[i] Mervosh, S., and Paris, F., “Why School Absences Have ‘Exploded’ Almost Everywhere,” The New York Times, March 29, 2024 – https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/03/29/us/chronic-absences.html

[ii] https://dpi.wi.gov/wisedash/about-data/chronic-absenteeism#:~:text=Students%20are%20considered%20to%20be,through%20their%20Student%20Information%20Systems

[iii] Borsuk, A., ““What Are We Willing to Do about Low-Performing Schools in Milwaukee Public Schools and Beyond? Right Now, There’s No Real Plan for Change,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, December 15, 2023 – https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/education/2023/12/15/no-apparent-play-to-help-improve-low-performing-mps-schools/71569628007

[iv] Will, Madeline, “This Leader Takes a Compassionate Approach to Truancy. It’s Transforming Students’ Lives,” Education Week, February 5, 2024 – https://www.edweek.org/leaders/leadership/this-leader-takes-a-compassionate-approach-to-truancy-its-transforming-students-lives/2024/02